Karachi confuses people sometimes even those who live in it.

The capital of Pakistans Sindh province, it is the countrys largest city a colossal, ever-expanding metropolis with a population of about 20 million (and growing).

It is also the countrys most ethnically diverse city. But over the last three decades this diversity largely consists of bulky groups of homogenous ethnic populations who mostly reside in their own areas of influence and majority, only interacting and intermingling with other ethnic groups in the citys more neutral points of economic and recreational activity.

Thats why Karachi may also give the impression of being a city holding various small cities. Cities within a city.

Apart from this aspect of its clustered ethnic diversity, the city also hosts a number of people belonging to various Muslim sects and sub-sects. There are also quite a few Christians (both Catholic and Protestant), Hindus and Zoroastrians.

Many pockets in the city are also exclusively dedicated to housing only the Shia Muslim sect and various Sunni sub-sects. Even Hindu and Christian populations are sometimes settled in and around tiny areas where they are in a majority, further reflecting the citys clustered diversity.

.

|

Police commandos petrol Karachis violent Kati Pahari (Split Mountain) area. One side of the hill is populated by Mohajirs and the other by Pakhtuns.

|

Most of those belonging to clustered ethnicities, Muslim sects and sub-sects and minority religions reside in their own areas of majority and they only venture out of these areas when they have to trade, work or play in the citys more neutral economic and cultural spaces.

The survival and, more so, the economic viability of the neutral spaces depends on these spaces remaining largely detached in matters of ethnic and sectarian/sub-sectarian claims and biases.

Such spaces include areas that hold the citys various private multinational and state organisations, factories, shopping malls and (central) bazaars and recreational spots.

Whereas the clustered areas have often witnessed ethnic and sectarian strife and violence mainly due to one cluster of the ethnic/sectarian/sub-sectarian population accusing the other of encroaching upon the area of the other, the neutral points and zones have remained somewhat conflict-free in this context.

The neutral points have enjoyed a relatively strife-free environment due to them being multicultural and also because here is where the writ of the state and government is most present and appreciated. However, since all this has helped the neutral zones to generate much of the economic capital that the city generates, these neutral spaces have become a natural target of crimes such as robberies, muggings, kidnapping for ransom, extortion, etc.

The criminals in this respect usually emerge from the clustered areas that have become extremely congested, stagnant and cut-off from most of the state and government institutions, and ravaged by decades of ethnic and sectarian violence.

Though the ethnic, sectarian/intra-sectarian, economic and political interests of the clustered areas are protected by various legal, as well as banned outfits in their own areas of influence, all these outfits compete with each other for their economic interests in the neutral zones because here is where much of the money is.

|

Karachis long Shahra-e-Faisal Road. One of the citys neutral zones.

|

Just why does (or did) this happen in a city that once had the potential of becoming a truly cosmopolitan bastion of ethnic and religious diversity, and robust economic activity in South Asia?

This can be investigated by tracing the citys political, economic and demographic trajectories and evolution ever since it first began to emerge as an economic hub more than a century and a half ago.

Birth of a trading post... and Paris of Asia

Karachi is not an ancient city. It was a small fishing village that became a medium-sized trading post in the 18th century. British Colonialists further developed this area as a place of business and trade.

Paris of Asia? Karachi (in 1910). Karachi was always a city of migrants. Hindus and Muslims alike came here from various parts of India to do business and many of them settled here along with some British. In the early 1900s, encouraged by the citys booming economy and political stability, the British authorities and the then mayor of Karachi, Seth Harchandari (a Hindu businessman), began a beautification project that saw the development of brand new roads, parks and residential and recreational areas. One British author described Karachi as being the Paris of Asia.

A group of British, Muslim and Hindu female students at a school in Karachi in 1910: Till the creation of Pakistan in 1947, about 50 per cent of the population of the city was Hindu, approximately 40 per cent was Muslim, and the rest was Christian (both British and local), Zoroastrian, Buddhist and (some) Jews.

Members of Muslim, Hindu and Zoroastrian families pose for a photograph before heading towards one of Karachis many beaches for a picnic in 1925: Karachi continued to perform well as a robust centre of commerce and remained remarkably peaceful and tolerant even at the height of tensions between the British, the Hindus and the Muslims of India between the 1920s and 1940s.

A British couple soon after getting married at a church in Karachi in 1927.

A group of traders standing near the Karachi Municipal Corporation (KMC) building in the 1930s.

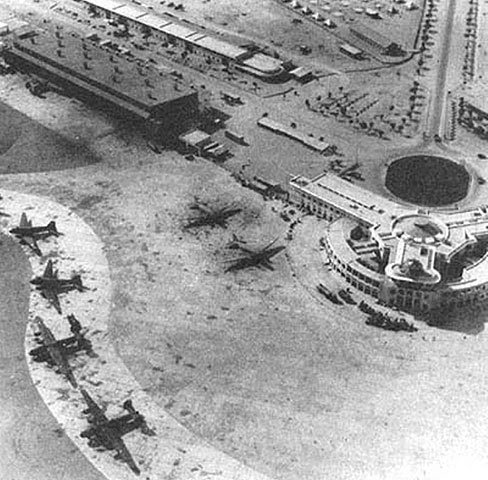

Karachi Airport in 1943. It was one of the largest in the region.

Karachis Frere Hall and Garden with Queen Victorias statue in 1942.

A 1940 board laying out the Karachi city governments policy towards racism.

Lyari in 1930 - Karachis oldest area (and first slum): Even though Karachi emerged as a bastion of economic prosperity (with a strategically located sea port); and of religious harmony in the first half of the 20th century, with the prosperity also came certain disparities that were mainly centred in areas populated by the citys growing daily-wage workers. By the 1930s, Lyari had already become a congested area with dwindling resources and a degrading infrastructure.

Shifting sands: Karachi becomes part of Pakistan

Karachiites celebrate the creation of Pakistan (August 14, 1947) at the citys Kakri Ground: The demography and political disposition of the city was turned on its head when the city became part of the newly created Pakistan. Though much of India was being torn apart by vicious communal clashes between the Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs at the time, Karachi remained largely peaceful.

A train carrying Muslim refugees from India arrives at Karachis Cantt Station (via Lahore) in 1948.

Hindus prepare to board a ship from Karachis main seaport for Bombay in 1948. To the bitter disappointment of Pakistans founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah (a resident of Karachi), the city witnessed an exodus of its Hindu majority. Jinnah was banking on the Hindu business community of the city to remain in Karachi and help shape the new countrys economy.

Commuters board a tram in Karachis Saddar area in 1951: As if overnight, the 50-40 ratio of the citys population (50 Hindu, 40 Muslim) drastically changed after 1947. Now over 90 per cent of the citys population was made up of Muslims with more than 70 per cent of these being new arrivals. A majority of the new arrivals were Urdu-speaking Muslims (Mohajirs) from various North Indian cities and towns. Since many of them had roots in urban and semi-urban areas of India and were also educated, they quickly adapted to the urbanism of Karachi and became vital clogs in the citys emerging bureaucracy and economy.

Karachis rebirth as the City of Lights

|

Karachis Burns Road in 1963: It grew into a major Mohajir-dominated area. By the late 1950s, Karachi began to regenerate itself as a busy and vigorous centre of commerce and trade. It was also Pakistans first federal capital. It was the only port city of Pakistan and by the 1960s it had risen to become the countrys economic hub.

Karachi 1961: Brand new buildings and roads in the city began to emerge in the 1960s. The government of Field Martial Ayub Khan that came into power through a military coup in 1958 unfolded aggressive industrialisation and business-friendly policies, and Karachi became a natural city for the government to solidify its economic policies.

The II Chundgrigar Road in 1962: It was in the 1960s that this area began to develop into becoming Karachis main business hub. It began being called Pakistans Wall Street.

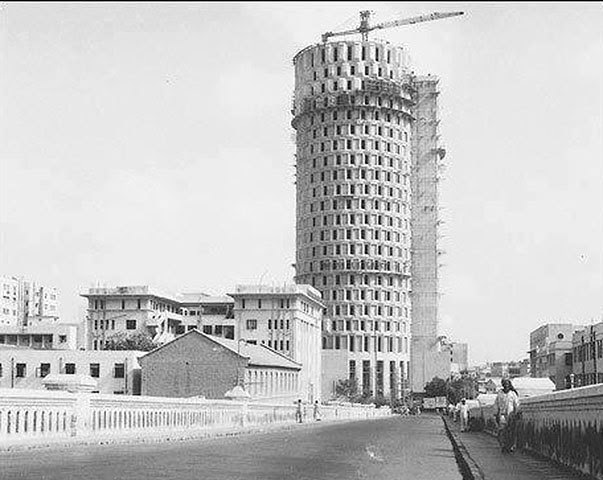

1963: Construction underway of the Habib Bank Plaza on Karachis II Chundrigarh Road. The building would rise to become the countrys tallest till the 2000s when two more buildings (also in Karachi) outgrew it.

Saddar area in 1965: Trendy shops, cinemas, bars and nightclubs began to emerge here in the 1960s and it became one of the most popular areas of Karachi. With Karachis regeneration as an economic hub, its traditional business and pleasure ethics too returned that consisted of uninterrupted economic activity by the day and an unabashed indulgence in leisure activities in the evenings.

|

A Pakhtun rickshaw driver at Karachis Clifton Beach in 1962. Though the Ayub regime moved the capital to the newly built city of Islamabad, the economic regeneration enjoyed by Karachi during the Ayub regimes first six years attracted a wave of inner-country migration to the city. A large number of Punjabis from the Punjab province and Pakhtuns from the former NWFP (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) began to arrive looking for work from the early 1960s onwards. But with the seat of power being moved from Karachi to Islamabad by the Ayub regime, the Mohajirs for the first time began to feel that they were being ousted from the countrys ruling elite.

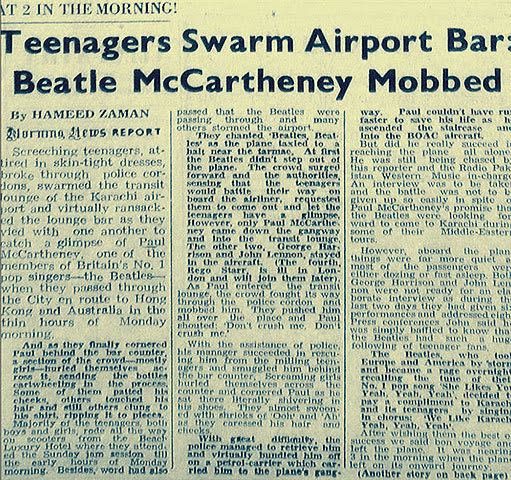

A 1963 newspaper clipping with a report on how Pakistani pop fans gate-crashed their way into a bar at the Karachi Airport where members of the famous pop band The Beatles were having a drink. They had arrived in Karachi to get a connecting flight to Hong Kong.

A local pop band playing at a nightclub in Karachi in 1968: It was during the Ayub regime that the term City of Lights was first used (by the government) for Karachi as brand new buildings, residential areas and recreational spots continued to spring up.

Western tourists shopping in the citys Saddar area in 1966.

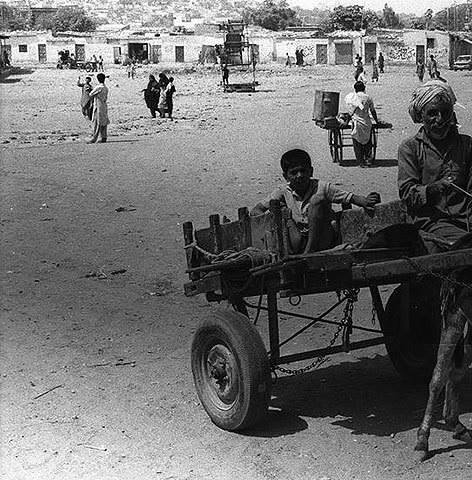

A donkey-cart owner and his son in Lyari (1967): Karachi once again became a city of trade, business and all kinds of pleasures, and yet, the industrialisation that it enjoyed during the period and the continuous growth in its population began to create economic fissures that the city was largely unequipped to address. The economic disparities and the ever-growing gaps between the rich and the poor triggered by the Ayub regimes lopsided economic policies became most visible in Karachis growing slums.

Many shanty towns like this one sprang up in the outskirts of Karachi in the 1960s. Criminal mafias involved in land scams, robberies, muggings and drug peddling in such areas found willing recruits in the shape of unemployed and poverty-stricken youth residing in the slums.

Police and military troops patrol the streets at Karachis Club Road area during a 1968 strike called by opposition parties against the Ayub government. Resentment against Ayub among the Mohajir middle and lower middle-classes (for supposedly side-lining the Mohajir community), and the growing economic disparities and crime in the citys Baloch and Mohajir dominated shanty towns turned Karachi into a fertile ground for left-wing student groups, radical labour unions and progressive opposition parties who began a concentrated movement against the Ayub regime in the late 1960s (across Pakistan). Ayub resigned in 1969.

Sleaze city: Fun and fire in the time of melancholia

Chairman of the left-wing PPP, ZA Bhutto addressing a rally in Karachi just before the 1970 election. The PPP became the countrys new ruling party in 1972. After the end of the One Unit (and separation of East Pakistan), Karachi became the capital of Sindh. Bhutto was eager to win the support of Karachis Mohajir majority. In various memos written by him to the then Chief Minister of Sindh, Bhutto expressed his desire to once again make Karachi the Paris of Asia.

|

Karachis Three Swords area in 1974. It was beautified during the Bhutto regime but today has become a busy and congested artery connecting Clifton with the centre of the city. It was during the Bhutto government that the citys first three-lane roads were constructed (Shara-e-Faisal), dotted with trees; the Clifton area was further beautified; foundation of the countrys first steel mill laid (in Karachi); and the construction of a large casino started (near the shores of the Clifton Beach) to accommodate the ever-growing traffic of European, American and Arab tourists.

A 1973 Karachi brochure for tourists who were visiting Karachi in the 1970s.

Tourists gathered outside a Tourist Information Office in Karachis PECHS area in 1972.

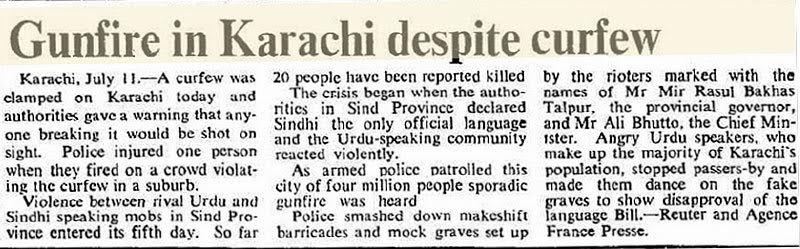

A newspaper report on the 1972 Language Riots in Karachi: Bhutto failed to get the desired support of the Mohajirs. This was mainly due to his governments socialist policies that saw the nationalisation of large industries, banks, factories, educational institutions and insurance companies. This alienated the Mohajir business community and the citys middle-classes. Also, since Bhutto was a Sindhi and the PPP had won a large number of seats from the Sindhi-speaking areas of Sindh, he encouraged the Sindhis to come to Karachi and participate in the citys economic and governing activities. This created tensions between the citys Mohajir majority and the Sindhis arriving in Karachi after Bhuttos rise to power.

The insomniac metropolis: The city that never slept

Karachi in the 1970s gave a look of a city in a limbo - caught between its optimistic and enterprising past and a decadent present. It behaved like a city on the edge of some impending disaster or on the verge of an existential collapse.

Most Karachiites would go through the motions of traveling to work or study by the day, and by night they would plunge into the various chambers of its steamy and colourful nightlife …

From elitist nightclubs …

… to seedy low/middle-income dance and drink joints, Karachiites looked to escape a melancholic existence by heading towards the citys many recreational outlets in the 1970s.

A 1973 press ad (in DAWN newspaper) of one of Karachis many famous nightclubs of the 1970s, The Oasis.

Nishat Cinema 1974: Cinemas in Karachi were usually packed with people in the 1970s.

Playland 1975: One of Karachis most famous recreational and amusement areas for families was the (now defunct) Playland.

Students at the Karachi University in 1973.

A group of students at the Karachi University in 1975.

Urdu news being delivered from Pakistan Televisions Karachi Studios (1974).

Crowd at a cricket Test match being played at Karachis National Stadium in 1976.

Karachis congested Merewether Tower area in 1976. A badly managed economy (through haphazard nationalisation), and the reluctance of the private sector to invest in the citys once thriving businesses strengthened the unregulated aspects of a growing informal economy that began to serve the needs of the citys population. The flip side of this informal economic enterprise was the creeping corruption in the police and other government institutions that began to extort money from these unfettered and informal businesses.

The rupture

Protesters go on a rampage during the anti-Bhutto movement in Karachis Nazimabad area (April 1977). In 1977 the city finally imploded. After a 9-party alliance, the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) that was led by the countrys three leading religious parties refused to accept the results of the 1977 election; Karachi became the epicentre of the anti-Bhutto protest movement.

A policeman beats up a protesting shopkeeper in the citys Saddar area during the PNA movement ( 1977). The protests were often violent and the government called in the army. The protests were squarely centred in areas largely populated by the Mohajir middle and lower middle classes. Apart from attacking police stations, mobs of angry/unemployed Mohajir youth also attacked cinemas, bars and nightclubs; as if the governments economic policies had been the doing of Waheed Murad films and belly dancers! The bars and clubs were closed down in April 1977.

|

Future MQM chief Altaf Hussain on a Karachi University bus (1977): As the PNA protests led to the toppling of the Bhutto regime (through a reactionary military coup by General Ziaul Haq in July 1977), within a year a group of young Mohajirs were already exhibiting their disillusionment with the PNA revolution. In 1978 two students at the Karachi University Altaf Hussain and Azim Ahmed Tariq - formed the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Organization (APMSO). They accused the religious parties of using the Mohajirs as ladders to enter the corridors of power while doing nothing to address the economic plight of the community.

Prosperity, piety, plunder

The American contingent parade past spectators at the 1980 Karachi Olympics: Zias dictatorship managed to strengthen itself soon after the Soviet forces invaded neighbouring Afghanistan in December 1979. Once the US resolved to oppose the Soviet invasion, it (along with Saudi Arabia), began pumping in an unprecedented amount of financial and military aid into Pakistan.

Foreigners enjoy a cruise on the waters of Karachis Kemari area in 1982.

Future US President Barak Obama visited Karachi as a visiting university student and stayed with a roommate of his in Karachi (1981).

Apart from the fact that Karachis university and college campuses exploded with protests against Zia (and then violent clashes between progressive student groups and the pro-Zia right-wing outfits), the city largely returned to normalcy and its status of being Pakistans economic hub was revived.

The continuous flow of aid helped the Zia regime stabilise the countrys economy. But underneath this new normalcy something extremely troubling was already brewing.

Since most of the sophisticated weapons from the US (for the Afghan Mujahideen) were arriving at Karachis seaport, a whole clandestine enterprise involving overnight gunrunners and corrupt police and customs officials emerged that (after siphoning off chunks of the US consignments), began selling guns, grenades and rockets to militant students (both on the left and right sides of the divide) and to a new breed of criminal gangs.

From the northwest of Pakistan came the once little known drug called heroin, brought into Pakistan and then into Karachi by Afghan refugees who began pouring into the country soon after the beginning of the anti-Soviet Afghan insurgency in Afghanistan…

The Taj Mahal Hotel 1982: A number of newly-built hotels sprang up in Karachi during the economic boom of the early 1980s. However, many critics were of the view that most of them were built with black money.

Poverty and drug addiction saw an alarming increase in Karachi in the 1980s.

1985: School and college students chant slogans against the government and Karachis transport mafia the day after a Mohajir student, Bushra Zaidi was run-over by a bus. The accident sparked a series of deadly riots between the Mohajirs and the Pakhtuns of Karachi.

|

Front-page news reports about the deadly 1986 Mohajir-Pakhtun riots in Urdu daily, Jang. As the armed student groups fought each other to near-extinction on the citys campuses, the violence, now heightened by sophisticated weapons, became the domain of criminal gangs in the citys Baloch and Pakhtun dominated areas. Most of these gangs had been operating as hoodlums peddling hashish, smuggled goods and running illegal prostitution dens in the 1970s. After the sale of alcohol (to Muslims) was banned in April 1977, they added the business of making and selling cheap whisky to their enterprise before they discovered the profitable wonders of selling guns and heroin. They were sometimes also used by political parties, as well as intelligence agencies for various political reasons.

Military personnel arrest a rioter in Karachis Orangi Town area in 1986. Working-class and lower-middle-class areas like Lyari and Orangi were the first two sections of the city to be hit by gang violence and heroin addiction in the 1980s.

The suddenly rich: Huge bungalows came up in the citys posh localities in the 1980s. A booming economy based on the continuous flow of financial aid arriving from the US and Saudi Arabia and generated by a somewhat anarchic form of capitalism paralleled urban prosperity with growing class disparities. It encouraged a free-for-all rush towards grabbing the chaotic political and economic fruits of such an economy.

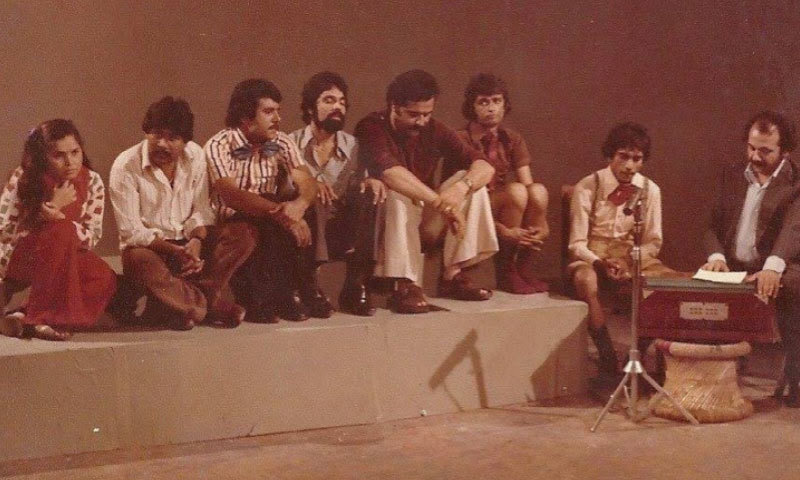

Team of PTVs social satire show, Fifty-Fifty often parodied the rise of greed and corruption and the social idiosyncrasies of the nonveau-riche that emerged from the 1980s anarchic brand of capitalism.

Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) chief, Altaf Hussain, speaking at a large party rally in Karachi in 1987. The mohajirs claimed that Karachis transport and real estate businesses had been taken over by gangs of Afghan gun and drug mafias and that the Mohajirs were being forcibly ousted from various areas of the city by refugees arriving in Karachi from Afghanistan. MQM decided to organise the Mohajir community into a cohesive ethnic whole.

A 1987 hoarding in Karachis Mohajir-dominated Nazimabad area. The deadly 1986 riots triggered the gradual formation of the citys clustered diversity (see first section) as Karachis various ethnicities began to reside in areas where their respective ethnicities were in a majority.

A wall in Lyari plastered with PPP posters in 1988. Lyari remained to be the partys main support base in Karachi. It also saw a number of anti-Zia protests throughout the 1980s.

Ziaul Haq during a visit to Karachi's busy shipyard: In the early 1980s, though Karachi did return to becoming the countrys economic hub again, this time much of its booming economics was based on a parallel black economy fuelled by the large amounts of money floated by drug, land and gun mafias. Instead of addressing such issues, the regime stuck to offering moralistic eyewashes through highly propagated and hyped postures of piety and certain draconian laws that were imposed in the name of morality and faith …

Women activists protesting against Zias moral policing outside the Sindh Chief Minister House in Karachi (1986).

Chairperson of the PPP and Zias leading opponent, Benazir Bhutto, waves to the crowd during her wedding ceremony (held in Lyari) in 1986.

In 1987 a massive bomb exploded in the busy Saddar area of the city, killing dozens of people. This was the first such incident in a Pakistani city and Karachiites were left shocked and badly shaken. The regime accused communist agents.

As the exhilaration of the superficial and contradictory economic boom experienced by the city in the early and mid-1980s began to recede, Karachi looked like a city in shambles with a rapidly growing population and a crumbling infrastructure. Its slums and many low-income areas were now crawling with drug peddlers and drug addicts and its lower-middle-class areas taken-over by armed youth, patrolling the streets, extorting money in the name of protecting the areas from possible hostile infiltration by members of enemy ethnicities. Prosperity had mutated into becoming paranoia.

Descent into chaos

A young MQM supporter wearing an Altaf Hussain T-Shirt in Karachis Liaqatabad area (1989). When the MQM swept the first post-Zia election in 1988 in Karachi, this was the first time (ever since the citys status as capital of Pakistan was withdrawn in 1962) that its representatives became a direct part of the government at the centre and in Sindh. The PPP had been returned to power in the election and it formed a coalition government with the MQM.

Benazir and Asif Zardari meet Altaf Hussain in 1989 to form PPP-MQM coalition governments in the centre and Sindh. The new government struggled to come to grips with the shock that the countrys economy and politics experienced after generous hand-outs from the US and Saudi Arabia began to dry out considerably at the end of the so-called anti-Soviet Afghan jihad.

A Pajero belonging to a leader of a religious leader in 1990 in Karachi: The cultural dynamics of the society had been radically altered. Amoral and cynical materialism nonchalantly ran in conjunction with a two-fold rise in the need and impulse to stridently exhibit ones piety.

Najeeb Ahmed the Karachi President of the PPPs student-wing, the PSF during a press conference in 1990. He was killed in an armed ambush: The permanent matter of Karachis ever-growing population, depleting resources and tensions between its various clustered ethnicities soon triggered a wave of violence as MQM and the PPP went to war in the streets and campuses of the city. The violence in Karachi became the pretext of the dismissal of Benazir Bhuttos first regime and the controversial election of Mian Nawaz Sharif as the new prime minister in 1990.

|

Nawaz, Altaf and Jam Sadiq at a rally in Karachi in 1991: Sharif vowed to turn Karachi into an economic hub again and for this he chose a former PPP member, Jam Sadiq Ali, as Sindhs new Chief Minister. Jam had been a member of the PPP till he was ousted by Benazir in 1986. Sharif used his grudge against the PPP to undermine the partys influence in Sindh. In Karachi, Jam gave a free hand to the MQM. Though MQM used this opportunity to launch a number of developmental projects in the citys mohajir-majority areas, at the same time it unleashed its activists against Jams enemies (both real and imagined).

|

COAS General Asif Nawaz (left) and Nawaz Sharif in Karachi in 1992: By 1992, with the countrys economy still showing no signs of recovery, and the corruption that first began to rear its head in the 1980s was continuing to grow, Karachi now truly looked like a crumbling city held hostage to the whims and tantrums of the MQM-Jam nexus. Alarmed by the situation, the military forced Nawaz to launch an operation against extortionists and MQM activists. Nawaz reluctantly agreed and in 1992 the operation was launched.

Cops encircle a dead body of an MQM activist in Karachis Burns Road area during the Govt-Military operation in Karachi in 1992: Karachi would see a total of three intense operations against the MQM across the 1990s. This decade is still said to be the most violent in the citys history. Hundreds of civilians, cops and members of paramilitary forces lost their lives.

Pakistan playing against South Africa at Karachis National Stadium during the 1996 Cricket World Cup.

A pop concert at Karachis KMC Complex in 1996.

1996: By the end of the 1990s, the citys infrastructure had almost completely collapsed, crippled by ethnic and political violence, strikes and curfews. Major businesses began to move out from the city, factories began to close down and incidents of extra-judicial killings, revenge murders, extortion and kidnapping became a norm. Heaps of garbage dumps unattended for months symbolised what had become of this once Paris of Asia and a bastion of economic ingenuity. The turmoil in the city finally came to a sudden end when General Pervez Musharraf toppled the second Nawaz Sharif government in 1999.

A brief interlude: The lights shine again

Musharraf distributing gifts to a child from one of Karachis slum areas in 2003. This was the year when the MQM regrouped and regenerated itself and got into an alliance with the Musharraf regime.

A fashion show being held at a Karachi hotel in 2003: In the first five years of his dictatorship, Musharraf managed to inject a sense of stability. Ethnic violence greatly receded, the economy bolstered, and neo-liberal capitalist manoeuvres strengthened the economic status of the middle-classes.